Growing up in the 1980s, one of the best things about Bank Holidays was a BBC Disney special on the TV. On a small screen, in your own home, you could see some of the best moments from classic Disney introduced by Lenny Henry or Dawn French. If you were really lucky, you’d get to watch the Bare Necessities from Jungle Book, or Everybody Wants to be a Cat from The Aristocats. If you were unlucky, you’d get Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boofrom Cinderella.

Either way, there was something special about Disney. What was in the secret sauce? And is it still there?

My own children have a hard time understanding this given we live with fibre internet, tablets and Disney+. Right now, my kids could decide to watch The Lady and the Tramp or 101 Dalmatians and be watching it in seconds. Back in the early 80s, even owning an expensive, toploading video recorder would not have helped. You couldn’t get Disney movies on video. In 1984, Disney released Robin Hood on VHS, a movie they held in low regard. It cost $80. If you wanted to watch a Disney movie, like Jungle Book or Bambi, you had to catch a re-release at a cinema. Either way, it was going to cost you.

One could say that the scarcity of Disney movies was part of their magical aura. But with hindsight, the determination to extract every last dime from their back catalogue looks rather defensive. Creatively it was a bad decade for Disney. The Fox and the Hound, slim pickings, was released in 1981. The next movie wasn’t for another four years. It was The Black Cauldron (nope, me neither), followed the next year by The Great Mouse Detective (I rewatched it recently. Poor.) and two years later, Oliver and Company, which seems to have vanished without trace.

How Walt Disney Bet Big and Won

Walt Disney must have been spinning in his grave. He’d founded the company in 1923, a hundred years ago. Although he and his brother had to scrap to survive, he ended up making huge creative bets. Looking back, it doesn’t look very risky to us. We live in a world where Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is a cultural touchstone, like Sergeant Pepper, An Inspector Calls or The Godfather.

But there was a time when these things didn’t exist – and no one asked them to exist. To create them requires vision. Walt Disney had that.

When asked about the secret of his success, Walt Disney explained his four Cs:

…curiosity, confidence, courage, and constancy, and the greatest of all is confidence. When you believe in a thing, believe in it all the way, implicitly and unquestionable.

Walt Disney must have seen something others did not in a curious and troubling tale by the Brothers Grimm, written in 1812. The movie left out some of the stranger details, like the Queen’s attempt to kill Snow White with a poisoned comb, and a more romantic ending was added.

Disney had always seen the comic potential of Seven Dwarfs. All dwarf names, and therefore attributes, were up for grabs. The seven dwarves could easily have been called Jumpy, Deafy, Dizzey, Hickey, Wheezy, Baldy, Sniffy and Swift. Or even Nifty, Lazy, Puffy, Stuffy, Tubby, Shorty, and Burpy. These were all considered. Finally, he pushed in all his chips on Sneezy, Happy, Sleepy, Grumpy, Dopey, Bashful and Doc. His whole enterprise would have been sunk if it had become anything other than an Oscar-winning box-office smashing hit. And the rest is history.

Except it isn’t.

How Disney Bet Big Again

Disney then bet the entire farm again on the off-beat celebration of classical music, Fantasia. Why not add Mickey Mouse to a story based on the 1797 poem by Goethe called Sorcerer’s Apprentice, set to the 1897 orchestral piece by Paul Dukas inspired by the original story? And then he did it again with Bambi, based on an unpromising novel for adults that was rather dark and grim, and released during World War Two.

Clearly success was not inevitable as things went wrong for Disney in the 1980s, as I explained above, before The Little Mermaid came along and changed everything in 1989, heralding a run of hit movies like Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994) and Pocahontas (1995).

So where did Walt Disney go right? And how does this relate to Disney’s latest woes in the culture wars?

Conservatives have been extremely vocal in the more progressive values depicted in live-action remakes like Peter Pan and Wendy, The Little Mermaid and Snow White (to say nothing of the seven dwarfs, because there aren’t seven dwarfs). One example would be Samuel Lively who explains that the real rot started with The Little Mermaid in his book, The Trojan Mouse.

Is Disney just attempting to cash in on their back catalogue yet again, whilst appeasing those who yell the originals were patriarchal, prejudiced and problematic?

Disney’s Vision

Perhaps we can see the secret of Walt Disney’s success at the box office by looking elsewhere: at his theme parks, and utopian visions of the future. Disney was always striving to not just imagine a better world, or draw one, but to physically build one. Historians might tell you that utopians are incredibly dangerous if they have money or power. (In fact, I’ve written about that here.)

Disney, however, was more interested in the vision than his own comfort, turfing out his family from their home in Palm Springs so it could be sold to pay for Disneyland to be finished. When it was done, he didn’t reap the rewards, but began thinking about Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, more commonly known as EPCOT.

Disney did not seem overly worried about the concerns – or even the values – of his day. He saw value in a strange 19th century German folk tale, and a futuristic monorail that took guests around his theme park. This may have been what made him deaf to those who complained bitterly about labour conditions in his animation studios. Maybe he was just mean.

But given his astonishing life of only 65 years, it’s more likely that he was someone taken with a greater vision of a better future. And the films of his era, at least, reflect that transcendent, multi-generational truth. No wonder Christians have always loved his legacy.

So How Has Disney gone wrong?

I wrote about Pixar in March last year which follows on from this article:

We Need To Talk About Pixar

Last Friday, I watched Pixar’s latest movie, Turning Red. I didn’t particularly want to but I was going to talk about it with my good friend, Nate Morgan Locke, for the Popcorn Parenting podcast. If you want to know what we made of it, you can listen to the episode here

Here’s that article on utopianism:

Building Utopia

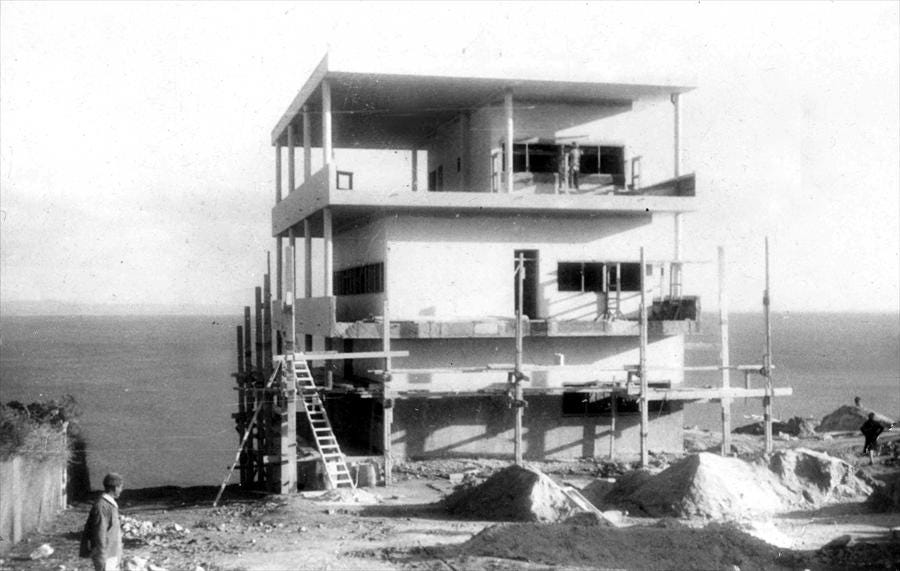

“We must refuse to afford even the slightest concession to what is: to the mess we are in now. There is no solution to be found there.” These are the words of Le Corbusier, an architect famous for designing houses (like the unfinished one below) that are striking, and fun to look at for a while, but you wouldn’t want to actually live in. It would be like…