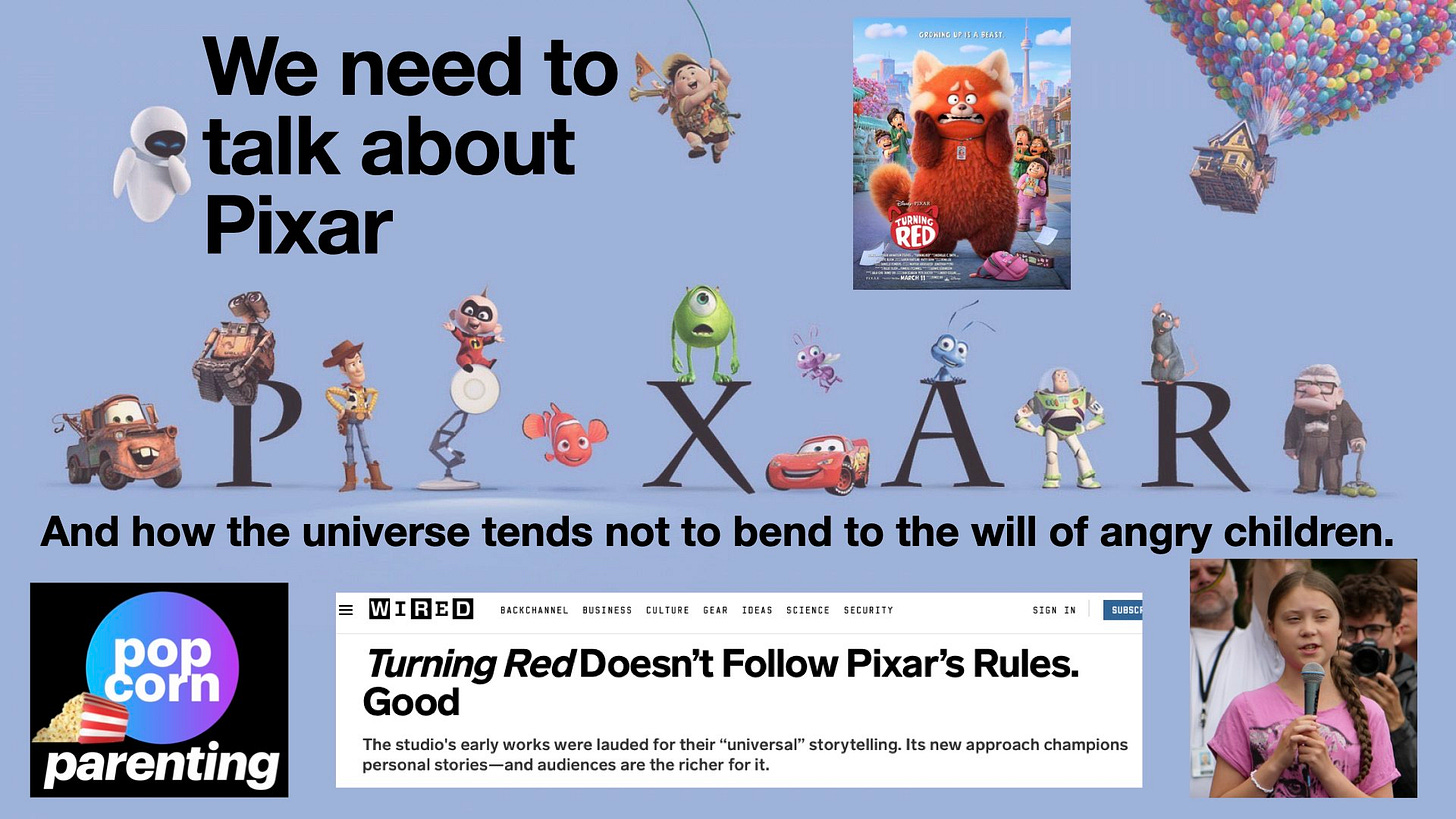

We Need To Talk About Pixar

And how the universe tends not to bend to the will of angry children.

Last Friday, I watched Pixar’s latest movie, Turning Red. I didn’t particularly want to but I was going to talk about it with my good friend, Nate Morgan Locke, for the Popcorn Parenting podcast. If you want to know what we made of it, you can listen to the episode here.

We followed up the episode with a more general chat about Pixar, which was a hit factory for a long time. Their first ten movies included Toy Story, Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc, Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Wall-E and Up. The inclusion of Wall-E in that list may be surprising, but on a second viewing, it became clear what an astonishing movie it is.

The other three from those first ten are A Bug’s Life, Cars and Ratatouille – decent films, but not compared the jaw-dropping standard of those other seven. Rewatching A Bug’s Life with my children a couple of years ago revealed that the movie didn’t bear repeat viewing like the others. Plus the really funny stuff is in the fake blooper reel at the end of the movie. Antz, released at the same time as A Bug’s Life, is more interesting, tackling the idea of the individual vs collectivism.

What Pixar Did Next

The next fifteen movies Pixar made are more of a mixed bag. Seven of them were sequels: Toy Story 3 & 4, Cars 2 & 3, Monsters University, Finding Dory and Incredibles 2. One vanished without a trace: The Good Dinosaur (nope, me neither). So that leaves Brave, Inside Out, Coco, Onward, Soul, Luca and now Turning Red.

So why wasn’t I keen to see Turning Red, why didn’t I enjoy it, and why wasn’t I surprised by that? Let’s think about that for a moment.

With That Attitude

Did I have the wrong attitude going in? Attitudes and expectations can be important when watching a movie. But I didn’t have high hopes for Onward and I loved it, watched it twice and want to see it again. And I was really excited about Soul, and wanted it to be good, and I hated it – and would argue that it is a very poorly constructed movie.

Target Audience?

One might also argue that I was never going to like Turning Red because it clearly wasn’t aimed at me – being about a Chinese-Canadian girl growing up and coming of age in Toronto in 2002.

But who are other Pixar movies aimed at? I’m more than capable of watching movies that aren’t about church-going English comedy writers who were raised on a dairy farm. Up was a movie about an old widower whose house is carried away by balloons. Finding Nemo is about fish. The Incredibles is about a family of superheroes. Wall-E is about two robots.

Turning Red, however, is another level of specificity and there’s a reason for that: the Pixar that released Toy Story in 1995 is not the Pixar releasing Turning Red in 2022. Pixar is no longer the scrappy plucky underdog. It is now a giant multi-national company with pension liabilities, shareholders, thousands of employees, a production schedule, an expectant audience around the world and an owner, Disney.

You can see that desire to appeal to audiences all over the world, as well as different ethnicities within North America. So we have Coco, Luca and Turning Red at Pixar, while Disney gave us Moana and Encanto.

Onward, a story about longing and loss, was pivoted away from the familiar western world to a semi-fantasy genre – and is none the worse for it. In fact, the setting is really interesting; a world that still has magic but just doesn’t use it any more because of, you know, science.

Given the number of movies produced in the last ten years, the representation of specific ethnicities doesn’t make up a huge number. Especially as we’ve had some more Toy Stories and Incredibles.

#TotesEmosh

These later movies, however, including the sequels, have a different quality or philosophy from the early ones. Some philosophical assumptions have worked their way through the academy, into the elites and then the artists and onto the big screen. And this is most obvious in Turning Red, Moana, Encanto and, the movie I’ve barely mentioned, Inside Out – which is explicitly about emotions.

Early movies had strong emotions - like Woody feeling intense threat from Buzz. But the question characters like that were asking was this: how do I reconcile my feelings – eg. my feelings of resentment of Buzz Lightyear – to reality, to the values of this world and to some kind of greater good? In the Toy Story world, we learn that life is not a zero sum game - and that all the toys belong to Andy who has enough love for all his toys. Woody does not change Andy’s mind or overturn the universe.

But Woody is a toy. Dory is a fish. Sully is a monster. Wall-E is a robot.

In the later movies, our heroes are much more commonly children. The universal layer of metaphor or allegory has dropped. And their emotions are a real and a self-validating truth that don’t need justification or mollification. In fact, they might require amplification.

Primal Scream

In Turning Red, the hero wants to go to the gig with her friends. What she wants is what she must have. The hero doesn’t change away from her new angry, duplicitous persona. Her friends say they like her this way. And so reality – and centuries of ancestral tradition - must change to meet the emotional needs of the protagonist.

And we see this in our wide culture. At COP26 last year, President Barack Obama told young people to ‘stay angry’ in the fight against climate change. Being generous, he says this so that people are motivated to make specific changes and alter the climate for the better.

But more often we’re presenting with the raw emotion, embodied in the Scandinavian ball of rage that is Greta Thumberg. Feel passionate enough for long enough and things will change. And if they’re not changing, you’re not angry enough and you don't care enough. This is simply not true. In fact, we used to say things like ‘The world does not revolve around you.’ Have we stopped saying that?

Who does change?

Technically, if movies are about people who go on a journey, Turning Red is about the mother and grandmother, who are ultimately changed by their daughter's emotional stubbornness. It’s a similar story with Encanto.

None of this seems to be a problem for critics. Some are celebrating that Turning Red is a break from the past for Pixar. The headline and summary of an article in Wired magazine is:

Turning Red Doesn’t Follow Pixar’s Rules. Good. The studio's early works were lauded for their “universal” storytelling. Its new approach champions personal stories—and audiences are the richer for it.

Turning Red has been given the thumbs up by all bar one of the top critics on Rotten Tomatoes who are beguiled by the freshness of the story, and the ethnic specificity of the world and protagonists.

But the real shift in Pixar is about the primacy of emotional truth, as opposed to revealed or objective truth. And that may be why this latest batch of movies jar with those of us who believe that humans beings are flawed, have unreliable emotions, need to calm down, repent and require supernatural spiritual help to be Christ-like.

For more discussion and the opportunity to hear Nate Morgan Locke finally come to terms with the movie that must not be named (Toy Story 4), have a listen to the Popcorn Parenting podcasts that are now on YouTube.

Here’s the one on Turning Red:

Here’s the one on Encanto:

Ahd here's our chat about Pixar: