I can still remember visiting the Science Museum and laying eyes on Stephenson’s Rocket. It is not, as the name suggests, a rocket but a steam locomotive that was, arguably, the workhorse of the Industrial Revolution, taking over from actual horses.

I was underwhelmed. This is not because I wasn’t impressed by the early steam engine leading to railways which became the backbone of Britain, and helped build an Empire. I simply assumed that the locomotive I was looking at clearly wasn’t the real thing. After all, if that was really Stephenson’s original Rocket, wouldn’t it have a room all to itself? Not placed in a cavernous hall with a bunch of other inventions and bits of scientific history? Nope. The museums of London are so embarrassingly well stocked, partly because of that Empire, that there just isn’t room to give individual items, well, entire rooms.

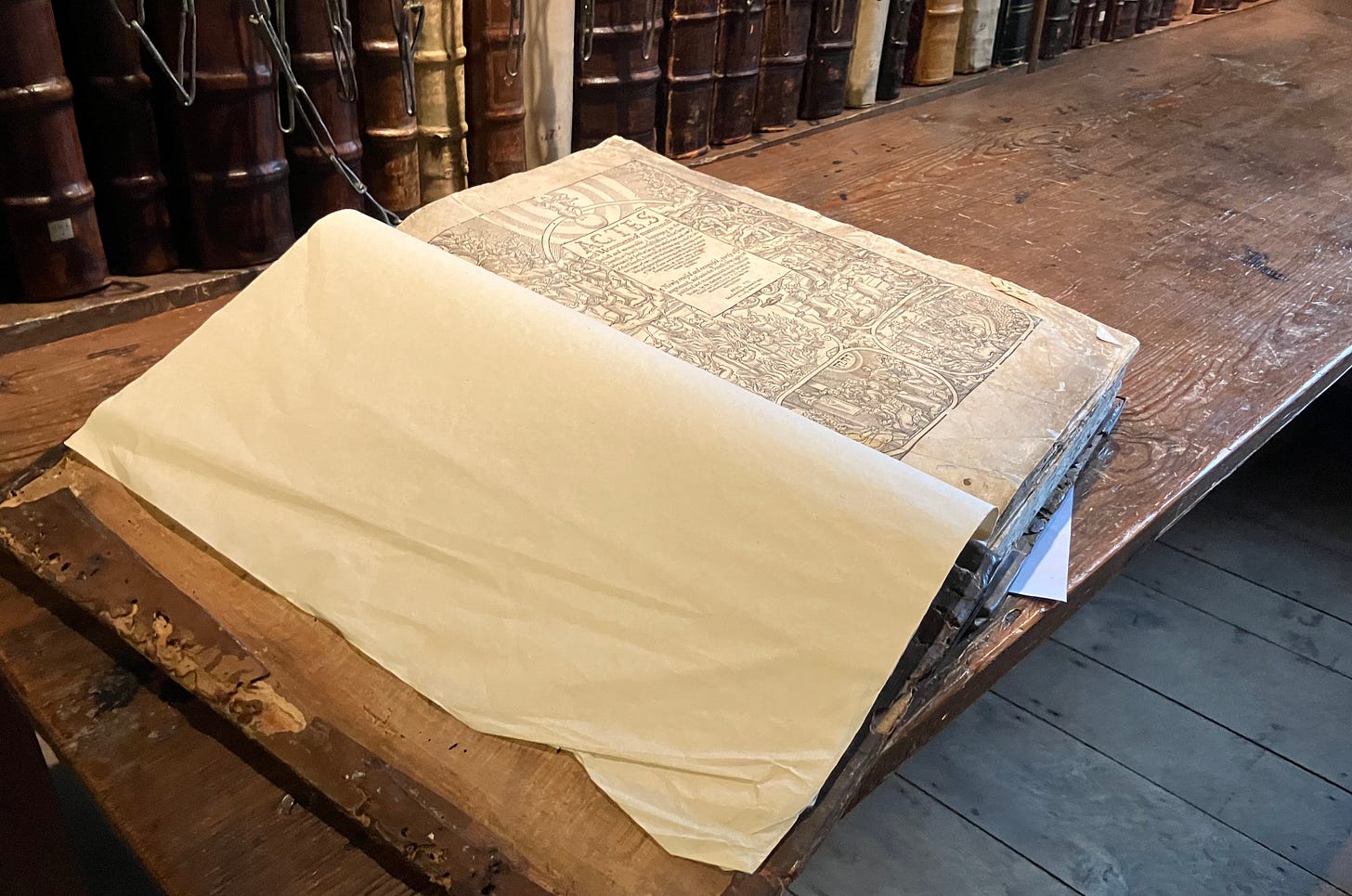

Sometimes, you don’t know what you’re looking at. Flash forward to October 2025. I’m in the Chained Library of Wells Cathedral because I know how to have a good time on my birthday. There I came face to face with a 1563 First Edition Acts and Monuments by John Foxe. I gasped. I could barely believe my eyes. I had not been prepared for this. And there it was, within touching distance. (No touching).

One lady on the tour had never heard of it. And you might be equally underwhelmed. That’s fair enough. It’s not a book much mentioned today, unlike Pilgrim’s Progress or The Canterbury Tales. The tour guide explained what it was: a catalogue of stories of Christian martyrs. In fact, it is better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. The impact of this book, I would argue, outstrips that of Stephenson’s Rocket. I really do mean that. Let me explain.

But first, let’s be clear on the contents of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. It is key source material for the great conflagrations of the 15th and 16th centuries that we’ve mentioned in previous posts here on Cary’s Almanac, including Hugh Latimer, William Sawtrey and William Tyndale. If you watch my YouTube documentary, you will also hear how many of Latimer’s friends like Barnes, Bainham, Bilney and Cranmer, went to the flames. These trials and executions are all recorded in the book.

Naturally, Foxe had picked a team. His book is a thoroughly Protestant account of the previous centuries, compiled in the early years of Elizabeth’s reign at “breakneck speed”, according to Foxe. The first edition was ready in 1563.

And there it was in the Chained Library in Wells Cathedral.

When the context of the book was explained to the group, the lady who had not known what it was laughed out loud. The very idea of the book seemed absurd. Why on earth should people burn each other over something as trivial or subjective as religion?

I would argue – in fact in a future post on Cary’s Almanac I will argue – that the only thing worth fighting over is religion.

But let us return to my previous statement about the impact of this book which did more to build the British Empire than Stephenson’s Rocket. The reason is not just down to the power of words, and stories, but the concerted attempt to remember them.

Acts and Monuments

The Elizabethan church was determined not to forget the price that had been paid for Protestantism. In fact, the clue is in the formal title: Acts and Monuments. These deeds were to be remembered. Queen Elizabeth, her ministers and her bishops realised the importance of this. In 1571, following the publication of the second, expanded edition, it was decreed that every archbishop, archdeacon, cathedral dean, and senior residentiary of every cathedral should possess a copy of Foxe’s book. Moreover, it had to be placed in a prominent location such as a hall or chamber for all to read. As a result, the book became one of the best-selling books in England for the following two centuries, surpassed only by The Bible and The Book of Common Prayer and, eventually, Pilgrim’s Progress.

Together, The Bible, The Book of Common Prayer (recited weekly by the English for centuries) and Foxe’s Book of Marytrs prepared a nation for both life and death. In fact, it helped the English put death and disaster into proportion, giving the English all kinds of motivation to export Christianity, Christendom and civilisation, at least as they saw it, all over the world.

Stephenson’s Rocket was a powerful locomotive engine. But engines need fuel. The British Empire had Anglican Christianity, a blend of Reformed Catholicism and Calvinism. A quotation attributed to Napoleon says, “I would rather meet ten thousand well-generalled and well-provisioned men than one Calvinist who thought he was doing the will of God.”

The Great Game

We see this in the tales of derring-do from outposts at the fringes of the British Empire. Read The Great Game by Peter Hopkirk, a book about the intrigue between Great Britain and Russia in the 19th century over India, and you will read jaw-droppingly epic voyages by British soldiers and diplomats across vast deserts and through dangerous passes to contact extremely dangerous tribes in Afghanistan, Persia, Tibet and China.

We won’t get into the various handwringing theories around colonialism here. What I’m interested in at this moment is how their actions and outlook are now often described as ‘stoic’. We picture the insouciant, unemotional gentlemen unruffled by danger, slaughter and chaos. By the time Noel Coward was singing comic ditties, this had already become a parable of itself.

It is not stoicism. It is Christianity. Many of these soldiers, diplomats and adventurers were professing Christians. Those who were only ‘culturally Christian’ were shaped by a Christianity refined by the fires of Foxe’s Acts and Monuments who realised that sacrifice was par for the course.

Bring Your Own Coffin

As missionaries in 1838, James and Mary Calvert were not unusual in shipping out to bring Christianity to disease-riddled Fiji with their possessions packed in coffins. Their ship’s captain warned them of the mortal dangers and the warring cannibalistic tribes to which Calvert replied, “We died before we came here.”

The Calverts were not stoics. They were Christians. They took seriously the words of Jesus who invited his followers to take up their cross, which means death. And they trusted Jesus when he said “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.” (John 11:25)

By the end of the 19th century, however, Christianity was already taken for granted, questioned, disbelieved or openly denied. We will come to that in future weeks here on the Almanac.

But the whole mission of this Almanac – as well as liturgical calendars, feast days and festivals – is remembrance. History may be written by the winner, but the victory doesn’t last unless anyone actually reads those history books.

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs was read and re-read by countless generations who wanted to be like those who submitted to the flames for a theological principle because they knew what they believed. And that’s why I told the story Hugh Latimer – and will tell other stories here on Cary’s Almanac.

Want to read more of those stories? Do you subscribe? It’s free and you can have it in your inbox every Friday lunchtime:

If you enjoyed the themes covered in this instalment of Cary’s Almanac, you will really like the conversation I had with Rhys Laverty on my podcast, The Stand-Up Theologian. We talk about that Noel Coward sense of absurdity at the English national character and why we simply refuse to take ourselves seriously. This has major upsides as well as downsides that aren’t very funny. Interested?

And here’s the Latimer doc. Seen it yet?

I like the way you are thinking about history from a Christian perspective. If I could make a minor suggestion, I think Noel Coward parodied Christians rather than made a parable of them...