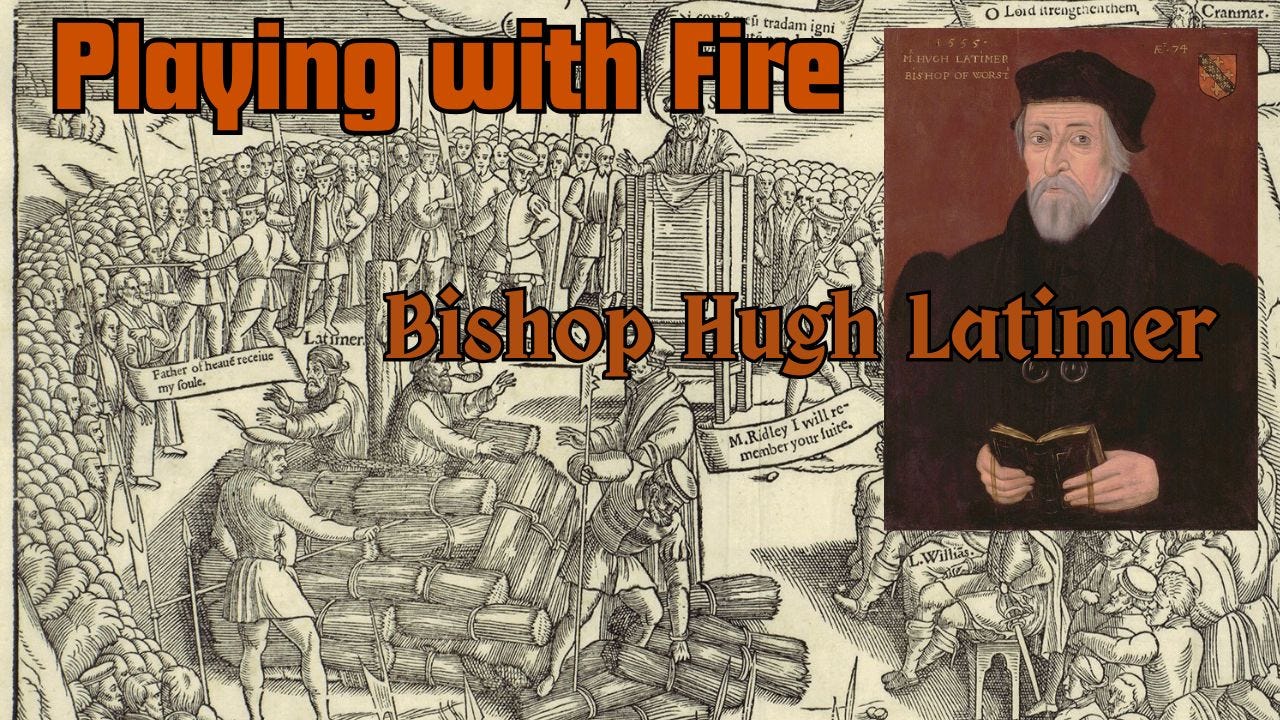

Playing with Fire

Introducing Bishop Hugh Latimer

I’ve spent much of this week writing about a man celebrated by the Church of England on 16th October: Bishop Hugh Latimer. That’s some weeks away, I realise, but a while back, I decided to make a YouTube video about Latimer which is currently under construction. Why did I choose Bishop Latimer?

He is famous for being burned as a Protestant reforming heretic in Oxford in 1555 along with Nicholas Ridley, former Bishop of London. But what attracted me to Latimer was his insouciant wit. On his way to the flames, according to Foxe, Latimer joked:

“Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man: we shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”

It’s not a brilliant joke, but context is everything. He’s about to be burned alive – having witnessed many of his friends suffer the same fate. What an astonishing thing to say. What sort of person says something like this?

I wanted to get to know Hugh Latimer, and I’m going to introduce you to him. Ready?

Hugh Latimer was a prime candidate to become a Protestant reformer. Born around 1485 to a yeoman farmer, he was not part of the elite class who wanted to keep the status quo. Rich families could use the established church to consolidate and extend their power, influence and income. The church was wealthy having been bequeathed money and land for the best part of a thousand years. King’s College Chapel in Cambridge, a place of worship for a few dozen students, is a giant example of the prosperity of the church in the late 15th century. Latimer was not part of that establishment. Would he join it and maintain it? Or seek to tear it all down?

Brought up rural Leicestershire, Latimer would have known all about the 14th century reformer John Wycliffe, who had lived in Lutterworth about twelve miles away. Would Latimer have a pre-disposition towards the teaching of the controversial academic and priest? For decades, Wycliffe wrote in condemnation of church corruption, superstition and the prevention of access to a Bible in English. Wycliffe was even condemned posthumously by the Church Council of Constance in 1414, his remains dug up, burned and thrown into the river. Latimer could have become captivated by the legacy of a local hero.

Latimer even followed in the academic tradition of Wycliffe, being sent off to university when his father realised that his son had a keen intellect and a way with words. So around 1506, he sent his son Hugh off to Clare College in Cambridge in the shadow of the enormous King’s College chapel next door. After gaining his bachelor’s degree, Latimer received Holy Orders but would remain in academia at Cambridge until 1531.

A Hotbed of Reform

This was a time of great change, and Latimer’s father could hardly have chosen a hotter bed of reform. Rapidly gaining a reputation as a place for new learning, Cambridge provided a temporary home for humanist scholar and critic of the church, Erasmus. This witty Renaissance man used fresh Greek manuscripts to improve the Latin translation of the New Testament which had remained virtually unchanged since the translation of Jerome a thousand years earlier.

Soon after Luther made his stand in Wittenberg against Indulgences in his 95 Theses, the works of Luther began to be discussed, Erasmus becoming a penpal of Luther with whom he initially had sympathy. There were glaring problems with the church. Even Cardinal Wolsey could see that whilst both embodying these problems but also seeking to reform them (as long as it didn’t affect his own bottom line, sphere of influence or dinner table).

The writings of Luther began to be discussed in Cambridge, mostly behind closed doors in hushed tones. One famous venue for these discussions was the White Horse Tavern, a pub that became known as ‘little Germany’. It was frequented by people like Thomas Bilney and George Stafford who were ‘early adopters’ of Lutheran thinking.

But Latimer was having none of it. He was vehemently opposed to the new learning and had no time for Erasmus. He even refused to learn Greek because it was the language of heresy (although he also studied Aristotle like a good medieval scholastic). He tried to persuade students not to attend the lectures of George Stafford, a fellow of Pembroke College, which would also become home to one Nicholas Ridley in 1524 who would become part of Latimer’s future and especially his end.

The Obstinate Papist

1524 is a key year for Latimer. He had been in Cambridge for nearly twenty years. Life was good. He was one of twelve University Preachers licensed by Cambridge, granting

him authority to preach anywhere in England. He also served in ceremonial roles at Cambridge, such as carrying the silver cross in academic processions. He’d arrived. He was respected was part of the establishment. Later he described himself an an “obstinate a papist as any was in England.”

Receiving his Bachelor of Divinity, he delivered a lecture against Stafford and the writings of Lutheran Reformer, Philip Melanchthon. Latimer was clearly a gifted preacher, but he used his talents to shore up the traditional teaching of the church, as expected.

That was all about to change. After this lecture, Latimer received a visit from a regular at the White Horse Tavern, Thomas Bilney who had experienced the same terror as Martin Luther at the consequences for his own sin. Bilney couldn’t fast for long enough, do enough penance or perform enough masses to relieve the burden of guilt he felt. He was very concerned for his own soul.

Erasmus’s new Latin translation of the New Testament, published in 1516, gave Bilney genuine divine revelation. He, like Luther and Augustine, discovered the teaching of Paul in his epistles about justification by faith. He wrote,

Immediately I felt a marvellous comfort and quietness, insomuch as my bruised bones leapt for joy.

As a result, his life was to be devoted to studying the scriptures. (In fact, a Bible which once belonged to Bilney is still preserved in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.)

It is this Bilney who knocks on the door of the esteemed preacher. Hugh Latimer later admitted that he vainly thought his lecture against Melanchthon had been so persuasive in favour of the old, traditional, Roman faith that Bilney was going to confess and recant. No. Bilney sensed a potential kindred spirit in Latimer, someone who genuinely believed and was hungry for the truth, “zealous without knowledge.”

Bilney was right. Latimer later admitted that he had been scrupulous in performing the mass lest he make a mistake and the sacrament be ineffective, imperilling his soul. Bilney gently introduced the joy of the scriptures to Latimer who realised they were words. Like Bilney, Latimer began to feel deliverance from endless penance, superstitions and the money-making activities of the church. Soon he would be publicly condemning them. Latimer had changed. In a sermon to Lady Katherine, Duchess of Suffolk in 1552, Latimer said this:

Master Bilney, or rather Saint Bilney,… was the instrument whereby God called me to knowledge; for I may thank him, next to God, for that knowledge that I have in the word of God.

Latimer’s pleasant life as an apologist and preacher for the establishment was over. And if you know one thing about the reign of Henry VIII, it is that political enemies and heretics did not last long. Bilney certainly did not. And he was far from the only one. Hugh Latimer was playing with fire.

If you’d like to know more about Latimer, stay tuned! In fact, subscribe. It’s free and every Friday.

The Stand-Up Theologian Podcast is LIVE!

The first episode of the The Stand-Up Theologian podcast has dropped. Here’s a four minute video introducing it:

Over my other site called The Wycliffe Papers, paid subscribers (Loyal Lollards) had already had access episode 2 about why atheism isn’t funny any more. And tomorrow they will get Episode 3 about The Life of Brian - early and extended. Loyal Lollards can also join the zoom chat about culture, comedy, church and the Bible. Why not upgrade to paid? Plus there are jokes over there like this one that I think Latimer would have found funny: