A running theme on this block is the power of fiction and story to explore ideas in a way that non-fiction simply cannot. It is often hard to put abstract ideas about our age into words, but then one reads a story that puts its finger on all kinds of interconnected thoughts.

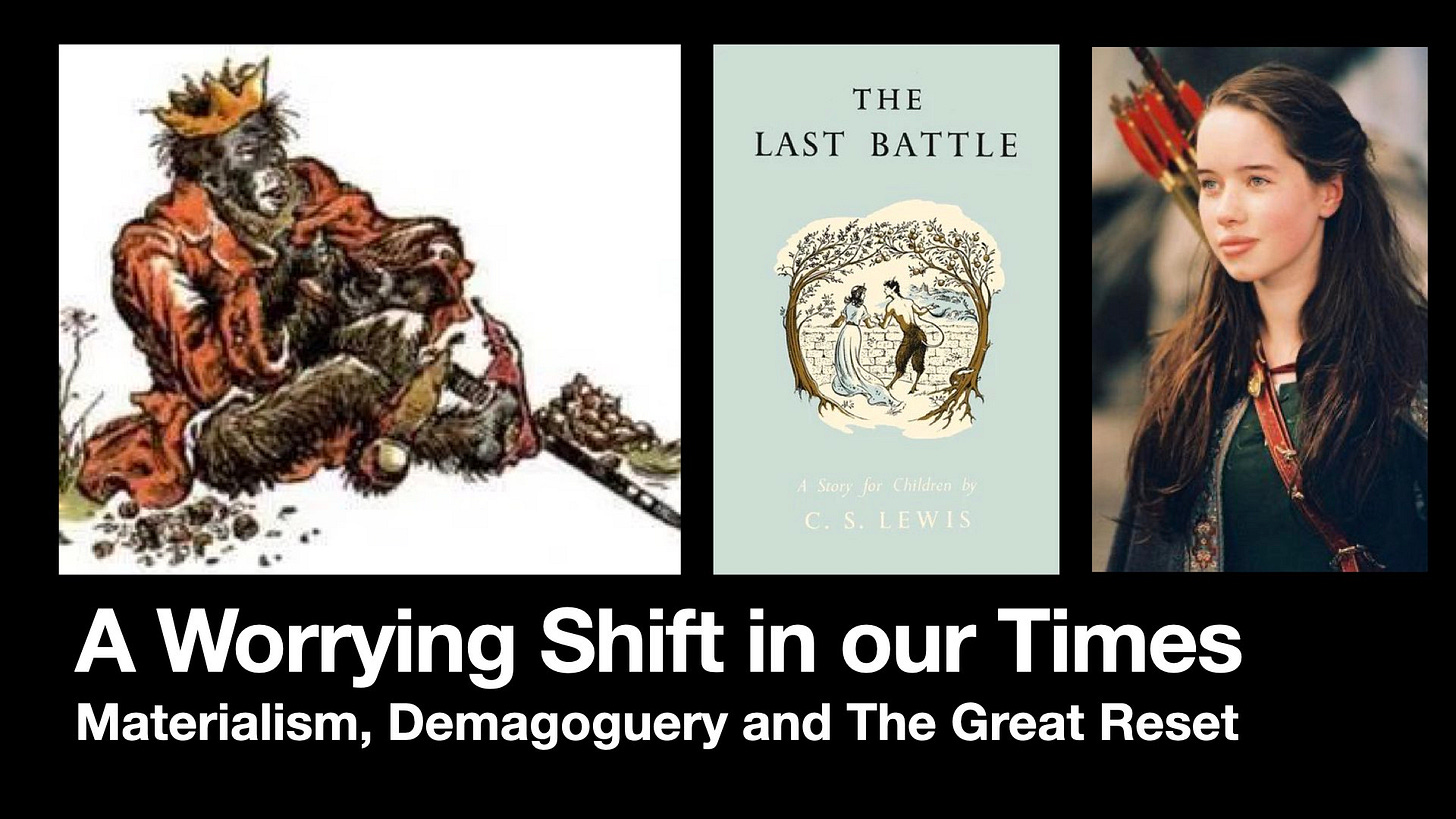

The fact that I’m struggling to introduce this article is a case in point. I might as well just write, “Oh, just go and read The Last Battle. That’s what I’m thinking right now. It is how I feel about our times, materialism, demagoguery and The Great Reset.”

But that’s not what you’ve come to this Substack for. So I have to be honest, and say I’m presenting three slightly connected thoughts that CS Lewis beautifully interlaces through the final book of the Narnia series, The Last Battle.

The book is not a cosy, comforting read. When one begins reading it, one realises straight away that it’s not a happy book, with no shortage of troubling scenes and moments of apocalyptic strangeness, which probably makes a lot more sense if you’re a medievalist, as CS Lewis was.

Thought 1: Desperately Seeking Susan

The first is right at the end. We read about the ecstatic relief of those who find themselves in the new creation.

“I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now...Come further up, come further in!”

But there is more than a tinge of sadness. Susan is not there, no longer being a ‘friend of Narnia’, as Eustace explains:

"whenever you've tried to get her to come and talk about Narnia or do anything about Narnia, she says 'What wonderful memories you have! Fancy your still thinking about all those funny games we used to play when we were children.'"

Modern readers get pretty angry about Susan’s exclusion, implying that CS Lewis was clearly some kind of misogynist. There are explanations for this omission that aren’t sinister. In the story, Susan was in America, and therefore not on the train when it crashed, sending the rest of her family back into Narnia and then into the new world. It seems quite possible she will find her way back.

But what if Susan were excluded? If we have a problem with Lewis, we have a problem with Jesus who told plenty of stories in which men and, yes, women find themselves shut out of feasts or banquets, or even unwilling to go. So there’s that.

Thought 2: Freedom Cold and Hard

Secondly, I’d like to mention a scene in the middle of the book that alarmed me in a way like no other moment in the Narnia stories. It was creepier even than reading about the demonic birdlike Tash, floating across the story. The scene I’m thinking of comes in Chapter 7 when a platoon of dwarfs is rescued from captivity by King Rilian, Eustace and Jill. The passage is unlike anything else in the rest of the Narnia books:

"Now, Dwarfs, you are free. Tomorrow I will lead you to free all Narnia. Three cheers for Aslan!"

But the result which followed was simply wretched. There was a feeble attempt from a few Dwarfs (about five) which died away all at once: from several others there were sulky growls. Many said nothing at all… The Dwarfs all looked at one another with grins; sneering grins, not merry ones.

"Well," said the Black Dwarf (whose name was Griffle), "I don't know how all you chaps feel, but I feel I've heard as much about Aslan as I want to for the rest of my life."

In short, we’re done with Aslan. Wow. That stings. A little later, Lewis goes on:

"Little beasts!" said Eustace. "Aren't you even going to say thank you for being saved from the salt-mines?"

"Oh, we know all about that," said Griffle over his shoulder. "You wanted to make use of us, that's why you rescued us. You're playing some game of your own. Come on you chaps."

And the Dwarfs struck up the queer little marching song which goes with the drumbeat, and off they tramped into the darkness.

Like so many today, the cynical dwarfs attribute everything to power games. To them, the only things that matters is independence. Detachment and autonomy is everything. Later in the book, they cry “the dwarfs are for the dwarfs,” refusing to be drawn into the fight against the evil presence of Tash – and are given a much diminished ‘reward’ when the world comes to an end, unable to perceive the beauty all around them.

Thought 3: Very Shifty

The dwarfs’ scepticism is not entirely without foundation, since we see the opposite state in the Last Battle: credulity. The terrified Narnian’s hang on every word and shudder at every threat issued by Shift, an Ape who has set himself up as a mouthpiece for a fake Aslan. Reading the book, one feels both sympathy for and frustration with the Narnians for going along Shift’s power games, falling for something that’s not even a dog and pony show. It’s a ape, cat and donkey show.

We encounter Shift at the very start of The Last Battle. He is a master of manipulation, persuading Puzzle the donkey to exhaust himself getting fine food for him, and risk illness and drowning by going after a lion’s skin. He even induces guilt in Puzzle for asking questions about Shift’s requests.

Shift is, for me, one of CS Lewis’ most masterful creations, and a character for our time: a self-serving, silver-tongued demagogue who will say anything to stay in power and reap the benefits of an elevated position.

We live in an age of Shift. Maybe we always have. Our political and cultural overlords will say anything to retain their positions of power. What was heresy a couple of years ago rapidly becomes dogma that has always been true. And it’s terrifying. Lewis writes it so well, there’s barely any point in explaining it. Lewis writes:

“There! You see!” said the Ape. “It’s all arranged. And all for your own good. We’ll be able, with the money you earn, to make Narnia a country worth living in. There’ll be oranges and bananas pouring in–and roads and big cities and schools and offices and whips and muzzles and saddles and cages and kennels and prisons–Oh, everything.”

“But we don’t want all those things,” said an old Bear. “We want to be free. And we want to hear Aslan speak himself.”

“Now don’t you start arguing,” said the Ape, “for it’s a thing I won’t stand. I’m a Man: you’re only a fat, stupid old Bear. What do you know about freedom? You think freedom means doing what you like. Well, you’re wrong. That isn’t true freedom. True freedom means doing what I tell you.”

Or, in the words of a video published by the World Economic Forum in 2016, “You will own nothing and be happy about it.”

CS Lewis put it so much better in fiction. And saw it all coming decades ago. Told you that you should just go and read The Last Battle.

Onward!

I’d not seen Pixar’s Onward when I recorded this episode of Popcorn Parenting with Nate, now re-released as a YouTube video. Since recording this, I’ve seen it a couple of times, and totally love it. One of Pixar’s finest, possibly challenging the podium containing Toy Story 2, The Incredibles and Wall-E.

In this episode, I mention an advert for a VW Polo that made me cry like a baby. And you know what? I recently bought a second hand red Polo, exactly like the one in this advert, with a view to my precious little daughter, now 15, being able to drive it in a couple of years. Talk about life imitating art.

And it’s only since rewatching it this year that I’ve noticed one key thing about the dad: what’s he doing for his daughter each time?

He’s protecting her. It’s beautiful. That’s what dads do. There’s probably a whole article on this, but there we go. Who says I don’t give value for (no) money?

Talking of Money

After Easter, there’ll be a chance to support this Substack by buying my ‘comedy special’ stand-up theology show, Water into Wine. It was video captured by the Speak Life team and I’ll be writing more about that next week - and several weeks after!